By Paolo Miguel

13 December, 2024

Introduction

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), the government organization charged with the protection and regulation of fishing practices, has announced that open-net pen salmon farms will be banned in 2029 because of the damage they cause to wild salmon populations. This will be a major setback for the industry, which will be forced to transition to closed containment farming on land or in smaller bodies of water with much less output. It will mark a major victory for the tourism industry that wants to preserve British Columbia’s natural beauty, for salmon fisheries that depend on wild salmon, and for First Nations who want to protect their food sources. However, this ruling might not be as effective as it seems.

Salmon Farming

The wild salmon’s reproductive cycle takes them on a long, arduous journey from rivers to oceans and back again, pushed by primal instinct towards spawning grounds far upstream, where their eggs will guarantee the survival of their population at the cost of their own lives. Salmon aquaculture condenses this complicated process into a few steps in a supply chain.

Salmon farming became an industry during the 1960s in cold-climate countries like Norway and only spread to British Columbia in the 1980s. Although science and technology have pushed the boundaries of productivity and efficiency, step-by-step operations have been mostly the same. In his book Salmon Farming: The Whole Story, author Peter A. Robson guides readers through the basics of salmon farming:

- Captive female salmon produce eggs, which are then harvested, treated for diseases, and disinfected if necessary, before being fertilized by male salmon.

- After the eggs hatch and the newborn fish become juveniles, their growth is carefully monitored for signs of smolting, a series of physical changes that prepare the salmon for the transition from the freshwater of rivers to the saltwater of oceans.

- Once the salmon have gone through this natural change, they are vaccinated to improve their survival rates in the ocean where they will spend the rest of their lives.

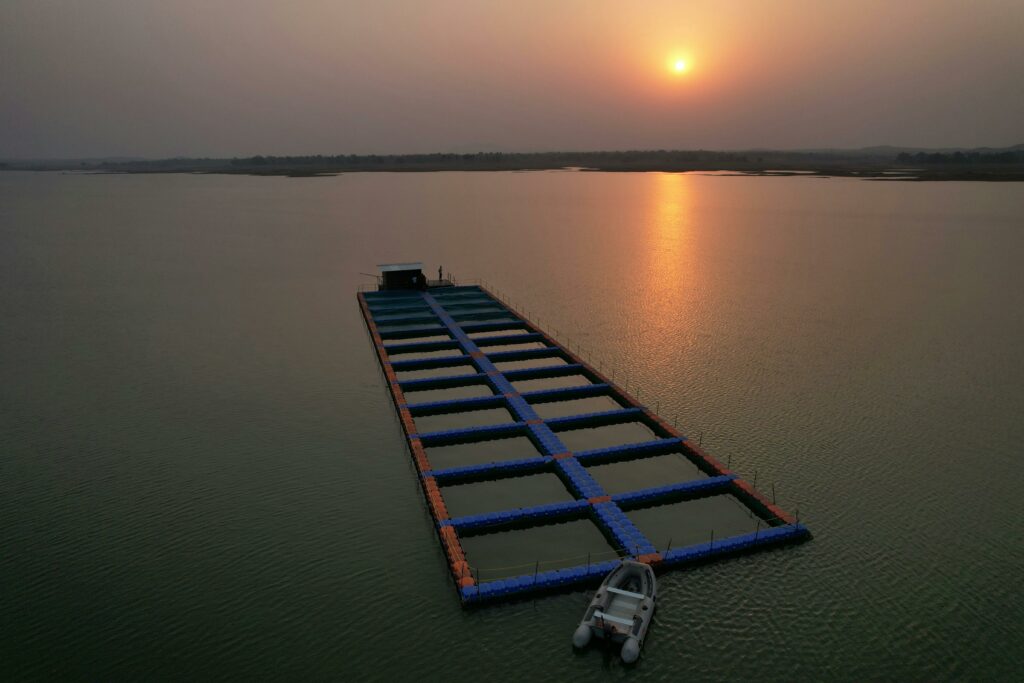

- The matured fish are transferred to seaborne enclosures called net pens. In its most basic form, a net pen consists of several logs floating in a circle to suspend a net in the water, like an enormous basket.

- The fish are fed, protected, and monitored until they reach harvestable size.

It’s an effective system that has created a thriving industry that benefits thousands and avoids many of the drawbacks associated with terrestrial farming, such as deterioration of soil quality and direct contribution to global warming. However, salmon farming hurts wild salmon populations. Net pens are a hotbed for sea lice, a common aquatic parasite that can wipe out entire enclosures of captive salmon if untreated. Although farmers can easily cure captive salmon by feeding them mildly poisonous food pellets, wild salmon receive no such benefit, allowing sea lice to spread unchecked and potentially devastate populations. These insects are small enough to slip through the net pens, strong enough to survive the open ocean, and resilient enough to latch onto wild salmon. This is the primary concern that led to the banning of open-net pens.

The Significance of Salmon

Salmon is a culturally and commercially important animal for British Columbia, where the environment is perfectly suited for wild and farmed populations. Many of the rivers that skim their fingers across BC’s coastlines and forests are salmon spawning routes. It is one of B.C.’s official symbols, and a vital food source for coastal First Nations communities.

According to Michael Pollan’s research in The Omnivore’s Dilemma, salmon is a comparatively cheap protein source that has the unique property of containing omega-3, a type of fat that has been proven to reduce the risk of cancer in humans. A government publication reported that salmon is one of British Columbia’s primary exports and is responsible for providing thousands of jobs, especially in coastal or remote areas where unemployment had been a problem before the advent of salmon aquacultures. Many First Nations peoples and territories are foundational for the industry, and government bodies like the DFO have regulated the involvement of foreign interests. Strict laws and policies are placed to control the impact of farms on communities and environments.

Left: Sashimi, photographed by Paolo Miguel

Many of these regulations were made at the birth of the salmon farming industry in the 1980s, but times have changed. Salmon is now a commodity whose output must be optimized to match stiff competition from the pioneering Norway and the less-regulated Chile. Salmon aquacultures in BC have become commercialized, with economies of scale and productivity becoming the focus. There is growing disregard for the environment, First Nations-owned territories, and wild salmon populations. Nowhere is this more emblematic than in the intrusiveness of open-net pens. For the wild salmon to survive, the captive salmon population must suffer. For farms to thrive, wild salmon populations will dwindle. If a middle ground exists, it veers dangerously close to the realm of compromise where neither party is satisfied.

What Have We Been Doing to Salmon?

Perhaps the greatest threat to both wild and captive salmon is humans. The demand for food has spilled over into excess, with food surpluses being more common than food shortages in some parts of the world, as evidenced by growing food wastage. As suggested in Food Security: From Excess to Enough by Ralph C. Martin, humankind no longer aims to feed the world—we feel the need to gorge ourselves. Corporations and governments have conspired to warp animals and habitats at a micro and macro level to meet those demands.

When salmon farming took off in British Columbia, operating costs rapidly increased as farms became more productive, leading prospective farmers to take bank loans. However, local banks were unwilling to invest in such new and unfamiliar territory. Norwegian banks, on the other hand, had much more experience in the industry and were willing to make those loans. The precious eggs integral to salmon farming also had to be outsourced from Norwegian producers, at least at first. Foreign interests, in the form of multinational corporations, continued to grow despite government regulations to slow them down. Today, 90% of all salmon farms in British Columbia are owned by 4 foreign companies, whose interests are more aligned with their bottom lines than any other stakeholder.

One major appeal of salmon to consumers is its abundant omega-3 content, but that is slowly being phased out as farmers are changing their fish feed. Salmon are carnivorous and require a certain amount of meat in their diet to grow to their full potential. This is an expensive food source that presents a drain on operating costs. In the past several years, some salmon have been gradually re-engineered to tolerate plant-based diets, which are cheaper to purchase and keep. Expenses go down, along with the salmon’s omega-3 and associated health benefits.

Human intervention in the salmon’s life cycle is not wholly bad. The vaccinations, antibiotics, and preventive measures against diseases needed to farm salmon at a commercial level allow aquacultures to restore dwindling wild salmon populations if necessary. Part of why Norwegian companies have a much deeper well of knowledge over other countries is due to a history of successful efforts doing just that.

Scientific and technological advancements have led to a boom in farmed salmon populations, to the extent that farmers need to take measures to avoid oversaturating the market with a flood of cheap salmon. Captive salmon are genetically modified to have their spawning cycles occur in the fall or winter and for newborn salmon to mature in the summer and fall. This allows farmers to avoid coinciding their harvests with wild salmon spawning cycles and ensure a year-round inflow of profits instead of a feast-or-famine cycle of surplus and shortage. This decision can be construed as corporate greed, but it also shows that farmers can maintain salmon populations if necessary. However, these accomplishments are only possible in part because of the government accommodations that have been made to make room for them.

Government Regulation

Since the very beginning of the industry, government regulation has often been lax or unfocused. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has long been accused of prioritizing salmon farms over wild salmon fisheries on the grounds of their failure to protect East Coast cod populations, the ‘disappearance’ of a million captive salmon, and the refunding of a $425,000 fine to salmon farms. However, this is also due in part to the difficulty of protecting wild salmon, whose habitat covers an enormous range of environments across oceans, rivers, forests, and mountains. Conserving all that ground is impractical at best, due to the various interests not only in aquacultures but also in logging, oil extraction, urbanization projects, and more, which pull their attention in every direction and into conflict with other industries. Ideally, the DFO would prevent any logging operations that would pollute rivers, but that would hurt the forestry industry’s lumber output, so concessions and compromises must be made. These may have minimal impact on salmon farms, but the wild salmon runs that need to traverse those rivers will be hurt. This is a deep-rooted dilemma that has historical precedent.

“The government’s policy is to hell with everyone else; get the logs out of the woods as cheaply as possible.”

Elgin ‘Scotty’ Neish

Riley Creek, a small stream in Graham Island, is home to a pink salmon run safe from human intervention. That changed in the late 1970s when a logging operation cut through the surrounding forest over several years. According to The Sustainability Dilemma by Griffin and Rajala, much of the conflict happened before the first tree was felled: when the Japanese-backed company that headed the effort proposed their siting, the DFO and the BC Ministry of Forests hesitated to give their approval. On the one hand, it presented an excellent opportunity to capitalize on a source of lumber and stimulate the economy. On the other, the logging would loosen soil and increase the already high likelihood of landslides that could clog Riley Creek and stop the salmon from reaching their spawning grounds. After much debate, protest, and lobbying, the logging operations proceeded, and the wild salmon population suffered. There was simply too much money to be made from the logging operations; more than would be made by preserving the salmon population. The whole affair can be summed up in the words of a disgruntled fisherman: “The government’s policy is to hell with everyone else; get the logs out of the woods as cheaply as possible.”

A similar problem is occurring today. The Malahat highway will be widened by as much as 1.6 kilometers to accommodate more vehicles and a barrier to improve road travel safety. This project would benefit all 25,000 vehicles that use it every day. However, these operations would also hurt the nearby Goldstream River, the salmon that live there, and the First Nations that rely on it as a food source. The project is set to continue, but protestors make their voices heard every day.

With a past and present of making impossible decisions, the ban on open-net pens was surprisingly decisive. Its consequences would be extensive, but there are preventive actions we can take to help reduce the uncertainty.

Implications and Further Actions

When the ban takes place, salmon farms will be forced to transition to less disruptive and productive aquaculture practices like closed containment farms. This will impact not only the foreign corporations that own most of these farms, but also the First Nations, coastal communities, and workers that rely on open-net pens for work. The DFO has identified these groups as the most impacted stakeholders and pledged to offer their support during that transitional phase, though no concrete results have come out of it thus far.

Although the ban will help protect wild salmon populations, it is only one of several factors that prevent their growth. Lumber, oil, and other natural resource extraction projects are unavoidable and will contribute to the destruction of wild salmon habitats and populations. Banning open-net pens is a start in the protection of wild salmon, and because the DFO can keep it contained within their purview, it is likely to pass without objection from other regulatory organizations. This is a bold step that will yield benefits.

Matters become much more complicated when working with other sectors’ affairs, especially when their priorities are so often at odds with each other. The best that British Columbians can do is understand the implications of every conservation and preservation effort on wildlife and their habitats; be they for logging or fishery. Nature is a complex system, and its protection is equally multifaceted. Any donations, charity, volunteer work, or promotion to aid in these efforts have direct benefits to specific causes and beyond. It is easy to miss the impact of these actions, but just as damaging the environment can have unexpected consequences, repairing it can have equally far-reaching benefits.

Thank You For Reading!

Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is

Proudly powered by WordPress

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.